- The Gatlin Brothers at Brown Country Music Center

- Kris Kristofferson passes away at 88

- The Magic Summer Tour: A Night of Nostalgia and New Memories

- Vlad Holiday at ACLfest 24: A Sonic Journey Through Indie Landscapes

- Cage The Elephant’s Resilience and Triumph at Noblesville Indiana: Review and Photos

- Lionel Richie and Earth, Wind, and Fire in Louisville: A review and photos

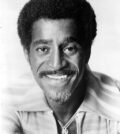

An Interview With “The Drum Doctor”

An Interview With “The Drum Doctor”

An Interview With “The Drum Doctor”

Drum Doctor Ross Garfield image from Bobby Owsinski’s Big Picture blog

We all know that the drums are the heartbeat of a song, and a wimpy drum sound will make the engineer work so much harder during the mix. That’s why it’s so important to get the drums to sound great acoustically before the mics are even placed. That said, it’s surprising how little many engineers actually know about making a drum kit sound great acoustically.

Here’s an excerpt from The Recording Engineer’s Handbook 3rd edition that features an interview with the famous “Drum Doctor” Ross Garfield, who’s been responsible for the actual drum sound on a multitude of huge records by some giant artists. Ross give some hints on how to take almost any kit and make it ready to record.

“Anyone recording in Los Angeles certainly knows about The Drum Doctors, the place in town to either rent a great sounding kit or have your kit fine-tuned. Ross Garfield is the “Drum Doctor” and his knowledge of what it takes to make drums sound great under the microphones may be unlike any other on the planet. Having made the drums sound great on platinum selling recordings for the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Rod Stewart, Mettalica, Marilyn Manson, Dwight Yokum, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Foo Fighters, Lenny Kravitiz, Michael Jackson, Sheryl Crow, and many more than what can comfortably fit on this page, Ross agreed to share his insights on drum tuning.

What’s the one thing that you find wrong with most drum kits that you run into to?

I think most guys don’t know how to tune their drums, to be blunt. I can usually take even a cheap starter set and get it sounding good under the microphones if I have the time. It’s really a matter of people getting in there and changing their heads a lot. Not for the fact of putting fresh heads on as much as the fact that they’re taking their drums apart and putting them back together and tuning them each time. The repetition is a big part of it. Most people are afraid to take the heads off their drums.

When I get called into a session that can’t afford to use my drums and they just want me to tune theirs, the first thing I’ll do is put a fresh set of heads on.

How long does it take you to tune a set that needs some help?

Usually well under an hour. If I have to change all the heads and tune them up it’ll take about an hour before we can start listening through the mics. I try to tune them to what I think they should be, then when we open up the mics and hear all the little things magnified, I’ll modify it. Once the drummer starts playing, I like to go into the control room and listen to how they sound when he plays, then once the band starts I’ll see how the drum sound fits with the other instruments.

What makes a drum kit sound great?

I always look for a richness in tone. Even when a snare drum is tuned high, I look for that richness. For example, on a snare drum I like the ring of the drum to last and decay with the snares. I don’t like the ring to go past the snares. And I like the toms to have a nice even decay. Usually I’ll tune the drums so that the smallest drums have a shorter decay and the decay gets longer as the drums get bigger. I think that’s pleasing.

What’s the next step to making drums sound good after you change the heads?

I tune the drums on the high side for starters. For tuning, you’ve got to keep all of the tension rods even so they have the same tension at each lug. You hit the head an inch in front of the lug, and if you do it enough times you’ll hear which ones are higher and which are lower. The pitch should be the same at each lug, then when you hit it in the center you should have a nice even decay. I do that at the top and the bottom head.

Are they both tuned to the same pitch?

I start it that way, and then take the bottom head down a third to a fifth below the top head.

I’ve been in awe of the way you can get each drum to sound so separate without any sympathetic vibrations from the other drums. Even when the other drums do vibrate, it’s still pleasing. How do you do that?

Part of that is having good drums and that’s the reason why I have so many; so I can cherry-pick the ones that sound really good together. The other thing is to have the edges of the shells cut properly. If you take the heads off, the edges should be flat. I check it with a piece of granite that I had cut that’s perfectly flat and about two inches thick. I’ll put the shell on the granite and have a light over the top of the shell. Then I’ll get down at where the edge of the drum hits the granite. If you see light at any point then you have a low spot. So that’s the first thing; to make sure that your drums are “true.”

The edges should be looked at anyway because you don’t want to have a flat drum with a square edge; you want it to have a bevel to it. If you have a problem with a drum, you should just send it in to the manufacturer. I don’t recommend anyone trying to cut the edges of their drums themselves. It doesn’t cost that much and it’s something that should be looked at by someone who knows what to look for.

Once you get those factors in play, then tuning is a lot easier. I tend to tune each drum as far apart as the song will permit. It’s easy to get the right spread between a 13 and a 16 inch tom, but it’s more difficult to get it between a 12 and a 13. What I try to do is to take the 12 up to a higher register and the 13 down a little. The trick to all that is the snare drum because the biggest problem that people have is when they hit the snare drum there’s a sympathetic vibration with the toms.

The way I look at that is to get the snare drum where you want it first because it’s way more important than the way the toms are tuned. You hear that snare on at least every two and four. The kick and snare are the two most important drums and I tune the toms around that and make sure that the rack toms aren’t being set off by the snare. The snare is probably the most important drum in the set because for me it’s the voice of the song. I try to pick the right snare drum for the song because that’s where you get the character.

Do you tune to the key of a song?

Not intentionally. I have people who ask me to do that, and I will if that’s what they want, but usually I just tune it so it sounds good with the key of the song. If there’s a ring in the snare, I try to get it to ring in the key of the song, but sometimes I want the kit just to stand on its own because if it is tuned in the key of the song and one of the players hit the note that the snare or kick is tuned to, then the drum kind of gets covered up, so I tend to make it sound good with the song rather than in-pitch with the song.

Would you tune things differently if you have a heavy hitter as opposed to someone with a light touch?

Yeah, a heavy hitter will get more low end out of a drum that’s tuned higher just because of the way he hits, so I usually tune a drum a little tighter. I might move into different heads as well, like an Emperor or something thicker.

How about the kick drum? It’s the drum that engineers spend the most time on.

It’s weird for me because I always find them to be pretty easy because you muffle the kick drum on almost every session and when you do, it makes tuning easier. On the other hand, a tom has as much life as possible with no muffling.

What I would recommend is to take a down pillow and set it up so that it’s sitting inside the drum touching both heads. From there you can experiment, so if you want a deader, drier sound then you push more pillow against the batter head, and if you want it livelier, then you push it against the front head. That’s one way to go.

Another way to go is to take 3 or 4 bath towels and fold one of them so it’s touching both heads. If that’s not enough then put another one in against both heads on top of the first one. If that’s not enough then put another one in. Just fold it neatly so that they’re touching both heads. That’s a good place to start, then experiment from there.

Do you prefer a hole in the front head?

It makes it easier. I do some things without holes in the front head, but having it really makes it easy to adjust anything on the inside. No front head is good too. It’s usually a drier sound and you’re usually just packing the towels against the batter head. Just put a sandbag in front to hold the towels against the head.

How about cymbals?

One thing for recording is that you probably want a heavier ride but you don’t want that heavy of a cymbal for the crashes. You also have to be careful when you mix weights. For example, if you’re using Zildjian A Custom crashes you don’t want to use a medium. You want to stay with the thins rather than try to mix in a Rock Crash with that because the thicker cymbals are made for more of a live situation. They’re made to be loud and made to cut and sometimes they can sound a little gong-like to the mics. On the other side of the coin, if you playing all Rock Crashes and the engineer can deal with the level, that’s not so bad either because the volume is even, but a thinner cymbal mixed in with those would probably disappear.

What records better; big drums or smaller ones?

I depends what you want your track to sound like. When I started my company, people would always say to me “Why would someone want to rent your drums when they have their own set?” For one simple reason; most drummers have a single set of drums. If they’re going for a John Bonham drum sound, they’re not going to get it with say a “Ringo” set. A lot of times when they go into the studio, the producer says, “You know, I really heard a 24” kick drum for this song. I hear that extra low end,” but the drummer’s playing a 22, so it’s important to have the right size drums for the song. If you’re going for that big double headed Bonham sound, you really should have a 26. If you’re going for a Jeff Porcaro punchy track like “Rosanna,” then you should probably have a 22. That’s my whole approach; you bring in the right instrument for the sound you’re going for. You don’t try to push a square peg into a round hole.

How much does the type of music determine your approach?

The drums that I bring for a hip-hop session are actually very close to what I bring for a jazz session. Usually the hip-hop guys want a little bass drum like an 18 and that’s what’s common for a jazz session, to have an 18 or a 20. Then maybe a 12 or a 14 inch rack tom, which is also similar to the jazz setup. The big difference is in the snare and hi-hats and the tuning of the kick drum and the snare.

On a jazz session I would keep the kick drum tuned high and probably not muffled. On a hip-hop record I would tune the kick probably as low as it would go and definitely not have any muffling so it has that big “boom” as much as possible. I would also have a selection of snares from like a 4 by 12 inch snare, 3 by 13 and maybe a 3 by 14. On a jazz record, I’d probably send them a 5 by 14 and a 6 1/2 by 14. The hi-hats on a jazz record would almost definitely be 14’s where a hip-hop record you’d want a pair of 10’s or 12’s, or maybe 13’s.

Obviously it’s open to interpretation because I’m sure a lot of hip-hop records have been made with bigger sets, but when I’ve delivered what I just said, it usually rocks their boat.

For more on The Drum Doctors, go to drumdoctors.com.”

You can read additional excerpt from The Recording Engineer’s Handbook and my other books on the excerpt section of bobbyowsinski.com.

Read more: http://bobbyowsinski.blogspot.com/#ixzz2qzDjzlrn

Under Creative Commons License: Attribution

0 comments