- Cirque du Soleil’s “Crystal” at Fishers Event Center, a photo preview

- The Gatlin Brothers at Brown Country Music Center

- The Black Keys will perform at Innings Festival, Feb 21.

- Gary Clark Jr. will rock the Innings Festival 2025

- Fall Out Boy to appear at Innings Festival in February

- Kris Kristofferson passes away at 88

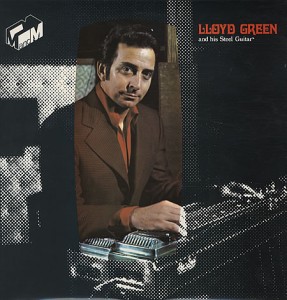

Meeting Mr. Nashville Sound: Lloyd Green

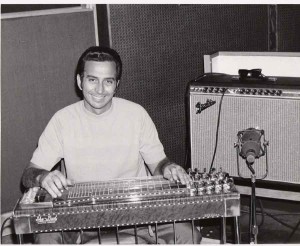

Nashville has a reputation for producing and coveting the nation’s most talented and versatile pickers. Among these legends is pedal steel player Lloyd Green, While may not be a household name in the grand scheme of things, the people whose albums he graces with his distinctive playing style certainly are: Paul McCartney, Ricky Skaggs, The Byrds, George Jones, Alan Jackson, Charley Pride, Tammy Wynette, Don Williams, Johnny Paycheck, and many more.

Green and I first got acquainted on the internet back in 2006 when we started exchanging emails regarding issues on the Steel Guitar Forum, a place where steel players chat online. Lloyd is not a member, so I would occasionally post for him when he needed to clarify a historical or musical issue related to him. During these exchanges Lloyd would tell me about his experiences, some of it jaw-dropping in its historical importance. Author Christopher Hjort used some of our correspondence in his 2008 book The Byrds: Day by Day, and gave us both a nod in the credits. So when a recent trip to Nashville brought me in close physical proximity to Mr. Green, I contacted him and asked if he would like to meet and shake hands. He agreed, and this is how he ended up in room 306 of the Comfort Inn on Demonbreun Street on a hot, beautiful Sunday morning in May 2011 to chat with a Newfoundlander on his virgin songwriting trip to Nashville.

Around 9:30am, after a late night on Lower Broadway with friend and co-writer Lennie Gallant, my phone rang. I rolled over and groggily answered. A charismatic, southern-tinged baritone voice greeted me: “Hey Chris…it’s Lloyd, man. You up? I’ve got to be in Franklin for noon or so. I was gonna swing on by about 10:30. Does that work for you?” Of course it worked for me, and after a quick shower and a bite to eat I went to the lobby to meet the man whose style I shamelessly copy every time I sit down behind my steel. Lloyd pulled up in a black Lincoln Town Car, parked it near the hotel’s main entrance, and walked toward me with an easy smile and his hand outstretched.

In his early 70s, Mr. Green is no doubt the envy of most men his age. Lean, quick on his feet, and handsome, Lloyd would easy pass for a man ten years his junior. We greeted each other warmly and retired back to my room where we pulled up a few chairs and settled in for a chat. I had been listening to the Byrds’ 1968 recording Sweetheart of the Rodeo, their now-legendary album that has been credited with starting the country-rock movement of the early ‘70s. Green played on the album. That’s him kicking off the lead track “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” with that gritty steel tone that many have since tried to emulate. He recalls: “I got the call to do the session at Columbia Studios in March of 1968. I had heard of the Byrds but wasn’t too familiar with their material. When I got there and set up, I asked them what they were looking for style-wise, and where they would like to me to play within the arrangements. They said, ‘Everywhere!’ I thought to myself, ‘These are my kind of guys!” He recounts this memory with a playful grin, seemingly revisiting a fond memory that has no doubt been summoned for recall many times. He talks about the Byrds playing the Opry and how he accompanied them from behind the curtain. The Nashville establishment, according to Lloyd, was not ready for the Byrds’ brand of “hippie” country, and they received a decidedly cold response both at the concert and around town in general. Lloyd disagreed with this prevailing attitude, and defended them to his peers whenever the occasion arose.

After the Nashville sessions, Gram Parsons called Lloyd from Los Angeles to ask if he would come to California to finish up two more tracks for the album. Busy with sessions, Lloyd nevertheless made room in his schedule and flew out on a weekend off. He was greeted at the airport by a limousine and taken directly to Columbia Studios where he immediately began tracking the last two songs for the album, “A Hundred Years From Now” and “All I Have Are Memories.” The latter turned out to be a showcase featuring him and B-Bender guitar virtuoso Clarence White. They trade off licks in this instrumental, each providing intricate, mind-bending runs and passages. They had only met that day, but they managed to find that special synergy very quickly – as seasoned pros often do. Forgetting White’s name for a second, I jog Lloyd’s memory and remind him. Lloyd responds, “Yes, Clarence White…that’s right. We had a great time. After the session he took me out to a club somewhere in a far-flung area of L.A. and we stayed there all night and hung out. Really nice guy.” (White would die several years later, tragically struck by a drunk driver as he was putting his guitar in the trunk of a car after an L.A. gig.)

When Sweetheart of the Rodeo was released a few weeks later, Gram Parsons and Roger McGuinn again called Lloyd at his Nashville home and asked if he would join the Byrds for a tour in support of the album. Gram mentioned jokingly that Lloyd would have to grow his hair out a bit. Lloyd respectfully declined the tour offer, citing his demanding studio session schedule as the reason. But Lloyd has no regrets about not going out on the road, always favoring the more secure and less stressful lifestyle of the studio player.

[youtube id=”nJQdR0ciwYg” width=”620″ height=”360″]

Similar offers would come his way as the 1970s rolled on. When Paul McCartney went to Nashville to record his countrified single “Sally G” in the mid-‘70s, Lloyd got the call. And when McCartney’s ensuing Wings Over America tour got rolling, Green’s phone once again rang: “It was Paul, asking me if I would do the Wings Over America tour with him. I told him about my obligations in Nashville. He pleaded that it was only two months, and that each night I would be featured in a stripped-down fifteen-minute country section consisting of Paul, Linda, Denny and me.” Still, it was not enough to lure Lloyd away from his bread and butter in Music City. Stunned yet respectful, McCartney wished Lloyd well and went on to stage what became one of the highest grossing tours of the decade.

Several years later, in 1980, McCartney once again called on Lloyd to record with him. This time it was in the middle of a tour Lloyd was doing in the UK that featured him as a solo artist. At the height of his fame, Lloyd Green had by now recorded several solo albums and was arguably the most well-known steel player in the world. McCartney sent for him by limo and Lloyd recorded at McCartney’s Essex mansion for the majority of a day off. Nearing midnight, Lloyd had recorded over twenty steel tracks for the workaholic McCartney when the phone rang in the studio: “Someone called with the news that John Bonham had died. The session wrapped up immediately and I took the limo with my wife back to London and continued on the tour.”

At that point in the conversation, I took a step back mentally to consider the gravity of this mid-morning conversation in my hotel room. I realized that I was sitting with a man who had weaved in and out of some of the most historically significant events in popular music history. Green jolted me out of my brief reverie by saying, “Enough about me. I’ve rambled too long. I want to know about you. Tell me about yourself.” So I told him about my music career and also the fact that I teach English at university. This impressed him greatly, it seemed. Articulate and well spoken, Green seems to greatly respect education – particularly the kind that promotes critical thinking. It is perhaps this kinship that allowed for us to connect in the way we did. Otherwise, I’m not sure why he would go out of his way to come visit yet another steel guitar admirer on a Nashville pilgrimage. I played some tracks for him on my stereo, some steel I had laid down for friend Barry Canning’s latest solo album. He sat on the edge of the bed and listened attentively, smiled when he recognized my occasional plagiarism of his licks, and stated with all honesty that he thought it was “world-class playing.” I sat there in silent awe, looking across the hotel bed at a man who had recorded in the best studios in the world with the biggest stars in music.

I later told him in a thank-you email that the experience of him listening to my steel tracks was akin to a guitar player having Eric Clapton approve a guitar solo. He enjoyed the analogy, telling me that Clapton had once summoned him to a VIP area after a show at Wembley Stadium to bestow his praises and ask if he was interested in recording with him in Nashville the following year. The session never transpired, but that doesn’t bother Lloyd. He chalks it up to the fanciful and fleeting whims of celebrity superstars.

Staying longer than he had planned, Lloyd checked his watch and realized his time was of the essence to get out to Franklin: “I have to pick up some material to learn for an upcoming session, so I’d better get going.” I walked him to his car where we lingered chatting for yet another ten minutes or so. When the wasps started to circle us, Lloyd saw it as a good time to bid adieu. We shook hands, embraced forearms, and smiled genuinely at what turned out to be a very warm and memorable 90 minutes of conversation.

0 comments