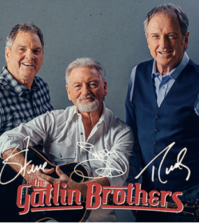

- The Gatlin Brothers at Brown Country Music Center

- Kris Kristofferson passes away at 88

- The Magic Summer Tour: A Night of Nostalgia and New Memories

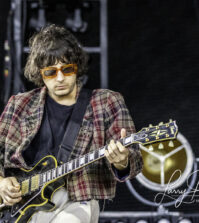

- Vlad Holiday at ACLfest 24: A Sonic Journey Through Indie Landscapes

- Cage The Elephant’s Resilience and Triumph at Noblesville Indiana: Review and Photos

- Lionel Richie and Earth, Wind, and Fire in Louisville: A review and photos

National Recording Registry’s Newest Additions

New National Recording Registry, with a Twist.

“Saturday Night Fever” album cover. Image courtesy of RSO

Chubby Checker, Saturday Night Fever, Janis, Simon and Garfunkel and more……………

“After You’ve Gone.” Marion Harris. (1918)

In one of the first recorded versions of this American standard, cabaret star Marion Harris, in a profound departure from then-current singing styles, sang in a relaxed, loose-limbed, near swinging style. Her performance matched perfectly the lyric of this unsentimental love song by Turner Layton and Harry Creamer, and also its sleek, blues-inflected melody and harmony. Layton and Creamer were part of a small group of African American songwriters to write for Broadway revues during the 1910s. This recording of “After You’ve Gone” led the transition in American popular singing from a full-throated, relatively stilted style, to a manner more relaxed, subtle and evocative.

In one of the first recorded versions of this American standard, cabaret star Marion Harris, in a profound departure from then-current singing styles, sang in a relaxed, loose-limbed, near swinging style. Her performance matched perfectly the lyric of this unsentimental love song by Turner Layton and Harry Creamer, and also its sleek, blues-inflected melody and harmony. Layton and Creamer were part of a small group of African American songwriters to write for Broadway revues during the 1910s. This recording of “After You’ve Gone” led the transition in American popular singing from a full-throated, relatively stilted style, to a manner more relaxed, subtle and evocative.

Image Caption: Marion Harris; Image Credit: LOC.

“Bacon, Beans and Limousines.” Will Rogers. (October 18, 1931)

Will Rogers had starred on the stage and screen and even made records, but when he entered radio broadcasting, it proved to be a natural medium for his folksy but pointed ruminations on topical matters. At one of the lowest points of the Great Depression, he took part in a national broadcast with President Herbert Hoover to kick off a nationwide unemployment relief campaign. Rogers praised Hoover’s integrity and intentions, but also decried the tragedy of such hard times in a land of plenty: “We’ll hold the distinction of being the only nation in the history of the world that ever went to the poor house in an automobile,” he observed. “The potter’s fields are lined with granaries full of grain. Now if there ain’t something wrong in an arrangement like that, then this microphone here in front of me is—well, it’s a cuspidor, that’s all.” The broadcast demonstrates the status Rogers had gained as a spokesperson for the “common man,” who used popular culture to satirize financial and political corruption, especially as the country went from the extravagant twenties into economic depression. Although Rogers is sardonic, the talk also conveys his fundamental optimism and faith in the good-heartedness of the American people.

Will Rogers had starred on the stage and screen and even made records, but when he entered radio broadcasting, it proved to be a natural medium for his folksy but pointed ruminations on topical matters. At one of the lowest points of the Great Depression, he took part in a national broadcast with President Herbert Hoover to kick off a nationwide unemployment relief campaign. Rogers praised Hoover’s integrity and intentions, but also decried the tragedy of such hard times in a land of plenty: “We’ll hold the distinction of being the only nation in the history of the world that ever went to the poor house in an automobile,” he observed. “The potter’s fields are lined with granaries full of grain. Now if there ain’t something wrong in an arrangement like that, then this microphone here in front of me is—well, it’s a cuspidor, that’s all.” The broadcast demonstrates the status Rogers had gained as a spokesperson for the “common man,” who used popular culture to satirize financial and political corruption, especially as the country went from the extravagant twenties into economic depression. Although Rogers is sardonic, the talk also conveys his fundamental optimism and faith in the good-heartedness of the American people.

Image Caption: Will Rogers; Image Credit: LOC.

“Begin the Beguine.” Artie Shaw & His Orchestra. (1938)

To have ended up as one of the indisputable classics of the Swing Era, “Begin the Beguine” had an inauspicious start. Cole Porter wrote it for the 1935 musical “Jubilee” which, despite good reviews, closed after a short run. Artie Shaw remarked on how close he came to not knowing about the song: “I happened to get to the theater on Friday and the show closed Saturday.” Shaw remembered the song, however, and in 1938, wanted to record “Beguine” in spite of its long, complicated structure. According to guitarist Al Avola, Shaw changed the usual slow tempo of a beguine to a 4/4 time called “bending the Charleston.” With some reluctance, RCA Victor, his new record company, allowed Shaw to release the recording as the “B” side to “Indian Love Call.” “Begin the Beguine” quickly became a hit and brought fame to Shaw and his band. Although Shaw became disenchanted with having to play “Begin the Beguine,” his de facto theme song, at every performance, the impact of this powerful recording of such a complex tune has remained a milestone in recorded sound history.

To have ended up as one of the indisputable classics of the Swing Era, “Begin the Beguine” had an inauspicious start. Cole Porter wrote it for the 1935 musical “Jubilee” which, despite good reviews, closed after a short run. Artie Shaw remarked on how close he came to not knowing about the song: “I happened to get to the theater on Friday and the show closed Saturday.” Shaw remembered the song, however, and in 1938, wanted to record “Beguine” in spite of its long, complicated structure. According to guitarist Al Avola, Shaw changed the usual slow tempo of a beguine to a 4/4 time called “bending the Charleston.” With some reluctance, RCA Victor, his new record company, allowed Shaw to release the recording as the “B” side to “Indian Love Call.” “Begin the Beguine” quickly became a hit and brought fame to Shaw and his band. Although Shaw became disenchanted with having to play “Begin the Beguine,” his de facto theme song, at every performance, the impact of this powerful recording of such a complex tune has remained a milestone in recorded sound history.

Image Caption: Artie Shaw; Image Credit: RCA.

“You Are My Sunshine.” Jimmie Davis. (1940)

Jimmie Davis, country music singer and two-term governor of Louisiana, adopted “You Are My Sunshine” for his successful 1944 election campaign after recording it in 1940. It subsequently became one of the most popular country music songs of all time and has been recorded by artists in the U.S. and abroad in many styles. At least three recordings preceded Davis’s, and while Davis is credited on sheet music as co-composer of the song, the song’s authorship is the subject of dispute. Davis’s recording, featuring guitar, steel guitar, trumpet, clarinet, bass, and piano, added jazz styling to the simple tune. “You Are My Sunshine” became the official song of Louisiana in 1977.

Jimmie Davis, country music singer and two-term governor of Louisiana, adopted “You Are My Sunshine” for his successful 1944 election campaign after recording it in 1940. It subsequently became one of the most popular country music songs of all time and has been recorded by artists in the U.S. and abroad in many styles. At least three recordings preceded Davis’s, and while Davis is credited on sheet music as co-composer of the song, the song’s authorship is the subject of dispute. Davis’s recording, featuring guitar, steel guitar, trumpet, clarinet, bass, and piano, added jazz styling to the simple tune. “You Are My Sunshine” became the official song of Louisiana in 1977.

Image Caption: Jimmie Davisr; Image Credit: LOC.

D-Day Radio Broadcast. George Hicks. (June 5-6, 1944)

The D-Day invasion was still secret when radio correspondent George Hicks committed his observations of it to a portable film recorder on the deck of a ship carrying troops to the beaches of France. The first official bulletins of the fighting aired in the early morning hours in the United States, but throughout the day the public had little more to go on than the occasional updates and speculation that filled radio airwaves. Hicks’s recording aired late that evening, and when his voice was heard over the din of combat, audiences found it riveting. Highlights were later released on 78-rpm records, and his spontaneous descriptions and composure under fire won him wide praise. Until this point, recordings had only very rarely been used in reporting the news, but as one commentator stated later that week, Hicks’s work showed that they could be “more alive than a ‘live’ program.”

The D-Day invasion was still secret when radio correspondent George Hicks committed his observations of it to a portable film recorder on the deck of a ship carrying troops to the beaches of France. The first official bulletins of the fighting aired in the early morning hours in the United States, but throughout the day the public had little more to go on than the occasional updates and speculation that filled radio airwaves. Hicks’s recording aired late that evening, and when his voice was heard over the din of combat, audiences found it riveting. Highlights were later released on 78-rpm records, and his spontaneous descriptions and composure under fire won him wide praise. Until this point, recordings had only very rarely been used in reporting the news, but as one commentator stated later that week, Hicks’s work showed that they could be “more alive than a ‘live’ program.”

Image Caption: George Hicks; Image Credit: NBC.

“Just Because.” Frank Yankovic and His Yanks. (1947)

As a child in Ohio in the 1920s, Frank Yankovic learned to play music of his parents’ Slovenian homeland on the accordion. By the 1930s though, Yankovic was playing in the polka style popular in Cleveland, a lightfooted and energetic fusion that incorporated influences from various Germanic and Eastern European traditions. Yankovic added flavoring from Italian, pop, jazz and other styles to this mix and experimented with the instrumentation as he built audiences. This eclectic approach served him well at his first major label recording session, when he insisted on recording “Just Because,” a country and western song of more than a decade earlier. Driven by the bright and melodic twin accordion leads of Yankovic and Johnny Pecon, and the jazzy inflection and syncopations of Hank Bokal’s drumming and Georgie Cook’s Dixieland tenor banjo, the pop and ethnic fusion of “Just Because” reached a national audience, and established Yankovic as polka’s top artist and innovator.

As a child in Ohio in the 1920s, Frank Yankovic learned to play music of his parents’ Slovenian homeland on the accordion. By the 1930s though, Yankovic was playing in the polka style popular in Cleveland, a lightfooted and energetic fusion that incorporated influences from various Germanic and Eastern European traditions. Yankovic added flavoring from Italian, pop, jazz and other styles to this mix and experimented with the instrumentation as he built audiences. This eclectic approach served him well at his first major label recording session, when he insisted on recording “Just Because,” a country and western song of more than a decade earlier. Driven by the bright and melodic twin accordion leads of Yankovic and Johnny Pecon, and the jazzy inflection and syncopations of Hank Bokal’s drumming and Georgie Cook’s Dixieland tenor banjo, the pop and ethnic fusion of “Just Because” reached a national audience, and established Yankovic as polka’s top artist and innovator.

Image Caption: Frank Yankovic; Image Credit: Columbia.

“South Pacific.” Original cast recording. (1949)

Acclaimed as one of Richard Rodgers’ and Oscar Hammerstein II’s greatest musicals, the Pulitzer Prize-winning “South Pacific” also has achieved landmark status in recorded sound history. Although the long-playing record (LP) was launched in 1948, sales did not take off until the next year, when Columbia Records released the original cast recording of “South Pacific” in both 78-rpm and LP formats. “South Pacific” became one of the best-selling records in the industry’s history and initiated a bidding war among record companies for the rights to record original cast albums. The show brought the subject of racial prejudice to a mainstream audience, and through the album, its message spread beyond Broadway to millions of American living rooms during the years in which the modern civil rights movement was spreading. Record producer Goddard Lieberson saw the show fourteen times while preparing the album, but realized that the most important decisions occurred in the recording studio itself. “It is there that ingenuity must substitute heightened musical effects for the action and scenery of the theatre,” he insisted. Lieberson’s goal to create during the recording session “the elusive quality of atmosphere” became the model for many great cast albums that followed “South Pacific.”

Acclaimed as one of Richard Rodgers’ and Oscar Hammerstein II’s greatest musicals, the Pulitzer Prize-winning “South Pacific” also has achieved landmark status in recorded sound history. Although the long-playing record (LP) was launched in 1948, sales did not take off until the next year, when Columbia Records released the original cast recording of “South Pacific” in both 78-rpm and LP formats. “South Pacific” became one of the best-selling records in the industry’s history and initiated a bidding war among record companies for the rights to record original cast albums. The show brought the subject of racial prejudice to a mainstream audience, and through the album, its message spread beyond Broadway to millions of American living rooms during the years in which the modern civil rights movement was spreading. Record producer Goddard Lieberson saw the show fourteen times while preparing the album, but realized that the most important decisions occurred in the recording studio itself. “It is there that ingenuity must substitute heightened musical effects for the action and scenery of the theatre,” he insisted. Lieberson’s goal to create during the recording session “the elusive quality of atmosphere” became the model for many great cast albums that followed “South Pacific.”

Image Caption: “South Pacifici” lp cover; Image Credit: Columbia.

“Descargas: Cuban Jam Session in Miniature.” Cachao Y Su Ritmo Caliente. (1957)

Inspired by the all-star jam sessions that Norman Granz organized and recorded for his Jazz at the Philharmonic series, Cuban bassist Israel “Cachao” Lopez, already a giant of Afro-Cuban music, sought to accomplish something similar with his peers in Havana. He brought musicians into the studio for two early morning sessions, when they were still fully charged up from their evening’s work in nightclubs and ballrooms. Rather than record long form jams, as Granz had done, the twelve musicians Cachao recruited created twelve short, spontaneous “miniature” pieces, each of which highlighted key instruments and facets of Afro-Cuban music. The resulting fusion blended African, European and American influences seamlessly. “Descargas”has had a lasting impact on Latin music, especially on the Salsa style that emerged in the 1960s, and Cachao organized many similar sessions for further albums both in Cuba and in the United States, where he settled after the Cuban revolution.

Inspired by the all-star jam sessions that Norman Granz organized and recorded for his Jazz at the Philharmonic series, Cuban bassist Israel “Cachao” Lopez, already a giant of Afro-Cuban music, sought to accomplish something similar with his peers in Havana. He brought musicians into the studio for two early morning sessions, when they were still fully charged up from their evening’s work in nightclubs and ballrooms. Rather than record long form jams, as Granz had done, the twelve musicians Cachao recruited created twelve short, spontaneous “miniature” pieces, each of which highlighted key instruments and facets of Afro-Cuban music. The resulting fusion blended African, European and American influences seamlessly. “Descargas”has had a lasting impact on Latin music, especially on the Salsa style that emerged in the 1960s, and Cachao organized many similar sessions for further albums both in Cuba and in the United States, where he settled after the Cuban revolution.

Image Caption: “Descargas” lp cover; Image Credit: EGREM.

Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto, No. 1. Van Cliburn (April 11, 1958)

Twenty-three-year-old Texas piano prodigy Van Cliburn won the prestigious International Tchaikovsky Piano Competition in Moscow in April 1958, charming a critical, but rapt Russian audience with this performance of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto, No. 1 in the finals. “Time” magazine noted that his competition appearance and subsequent concert tour of the Soviet Union, broadcast over radio and television, “has had more favorable impact on more Russians than any U.S. export of word or deed since World War II.” Composer Aram Khachaturian stated, “you find a virtuoso like this only once or twice in a century.” Although Cliburn later recorded the Concerto for an RCA Victor commercial release that enjoyed immense popularity, the archival recordings from the finals of the competition convey the sense of Cold War history in the making.

Twenty-three-year-old Texas piano prodigy Van Cliburn won the prestigious International Tchaikovsky Piano Competition in Moscow in April 1958, charming a critical, but rapt Russian audience with this performance of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto, No. 1 in the finals. “Time” magazine noted that his competition appearance and subsequent concert tour of the Soviet Union, broadcast over radio and television, “has had more favorable impact on more Russians than any U.S. export of word or deed since World War II.” Composer Aram Khachaturian stated, “you find a virtuoso like this only once or twice in a century.” Although Cliburn later recorded the Concerto for an RCA Victor commercial release that enjoyed immense popularity, the archival recordings from the finals of the competition convey the sense of Cold War history in the making.

Image Caption: Van Cliburn; Image Credit: Testament.

President’s Message Relayed from Atlas Satellite. Dwight D. Eisenhower. (December 19, 1958)

On December 18, 1958, the U.S. launched into orbit the world’s first communications satellite in response to the Soviet Union’s successful orbiting the previous year of Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite. Sputnik had panicked many Americans, who worried about that the U.S. was losing the space race and that the nation’s science, education, and defense establishment were failing. Although he was not impressed by Sputnik, President Dwight D. Eisenhower responded to these anxieties by reluctantly increasing defense spending. Created under the auspices of the Defense Department’s newly formed Advanced Research Projects Agency, Project SCORE, carried by an Atlas satellite, transmitted a prerecorded message by Eisenhower the day after its launch that was heard on ground stations via shortwave radio after signals from earth had triggered a tape recorder aboard the craft. The President’s greeting was succinct, conveying peaceful wishes to the whole world. The launch, the first time a missile guidance system steered a satellite into orbit, and the transmission of the president’s message was promoted as a major propaganda victory. Project SCORE spurred developments in telecommunications, and in July 1962, the Telstar satellite relayed the first television images.

On December 18, 1958, the U.S. launched into orbit the world’s first communications satellite in response to the Soviet Union’s successful orbiting the previous year of Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite. Sputnik had panicked many Americans, who worried about that the U.S. was losing the space race and that the nation’s science, education, and defense establishment were failing. Although he was not impressed by Sputnik, President Dwight D. Eisenhower responded to these anxieties by reluctantly increasing defense spending. Created under the auspices of the Defense Department’s newly formed Advanced Research Projects Agency, Project SCORE, carried by an Atlas satellite, transmitted a prerecorded message by Eisenhower the day after its launch that was heard on ground stations via shortwave radio after signals from earth had triggered a tape recorder aboard the craft. The President’s greeting was succinct, conveying peaceful wishes to the whole world. The launch, the first time a missile guidance system steered a satellite into orbit, and the transmission of the president’s message was promoted as a major propaganda victory. Project SCORE spurred developments in telecommunications, and in July 1962, the Telstar satellite relayed the first television images.

Image Caption: Dwight D. Eisenhower; Image Credit: LOC.

“A Program of Song.” Leontyne Price. (1959)

Leontyne Price’s debut recital recording, “A Program of Song,” recorded in 1959 at Town Hall in New York, showcases the soprano’s beautiful, well-balanced voice that had been garnering praise since the early 1950’s. As a student at the Juilliard School of Music she caught the attention of Virgil Thomson and was invited to sing the role of Saint Cecilia in the 1952 revival of his “Four Saints in Three Acts.” Success soon followed with U.S. and European tours and debuts in opera houses around the world. Known for her insightful and adventurous musicianship, as well as the dramatic feeling she brought to roles, in 1960, Price became the first African American to sing a leading role, Aida, at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan. “A Program of Song,” featuring renditions of French and German works by Gabriel Fauré, Francis Poulenc, Richard Strauss and Hugo Wolf that are considered to be among the most challenging of vocal pieces, revealed to listeners at home an artist of amazing power, range and depth.

Leontyne Price’s debut recital recording, “A Program of Song,” recorded in 1959 at Town Hall in New York, showcases the soprano’s beautiful, well-balanced voice that had been garnering praise since the early 1950’s. As a student at the Juilliard School of Music she caught the attention of Virgil Thomson and was invited to sing the role of Saint Cecilia in the 1952 revival of his “Four Saints in Three Acts.” Success soon followed with U.S. and European tours and debuts in opera houses around the world. Known for her insightful and adventurous musicianship, as well as the dramatic feeling she brought to roles, in 1960, Price became the first African American to sing a leading role, Aida, at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan. “A Program of Song,” featuring renditions of French and German works by Gabriel Fauré, Francis Poulenc, Richard Strauss and Hugo Wolf that are considered to be among the most challenging of vocal pieces, revealed to listeners at home an artist of amazing power, range and depth.

Image Caption: “A Program of Song” lp cover; Image Credit: RCA Victor.

“The Shape of Jazz to Come.” Ornette Coleman. (1959)

On his debut for Atlantic Records, Ornette Coleman pushed the boundaries of jazz even further into the unknown than he had on his earlier efforts for Contemporary Records. Critic Ralph J. Gleason observed that “the musical and critical world [was] split neatly in two” by Coleman’s willingness to abandon bebop’s harmonic structure and timing when his music required it. What Coleman never abandoned was the centrality of improvisation to jazz. In this effort he is ably assisted by Don Cherry on cornet, Charlie Haden on bass and Billy Higgins on drums – all musicians with whom he had played intermittently for several years. Cherry and Coleman achieve a close interaction on several tracks, particularly in their speedy unison playing at the beginning of “Eventually” and “Congeniality.” Haden not only accompanies the other musicians, but also stretches the melodic potential of his instrument, particularly in his solo on “Focus on Sanity.” For all the record’s iconoclasm, it swings, and even Coleman’s more outrageous timbral experimentation can be understood as rooted in the expressiveness of the blues.

On his debut for Atlantic Records, Ornette Coleman pushed the boundaries of jazz even further into the unknown than he had on his earlier efforts for Contemporary Records. Critic Ralph J. Gleason observed that “the musical and critical world [was] split neatly in two” by Coleman’s willingness to abandon bebop’s harmonic structure and timing when his music required it. What Coleman never abandoned was the centrality of improvisation to jazz. In this effort he is ably assisted by Don Cherry on cornet, Charlie Haden on bass and Billy Higgins on drums – all musicians with whom he had played intermittently for several years. Cherry and Coleman achieve a close interaction on several tracks, particularly in their speedy unison playing at the beginning of “Eventually” and “Congeniality.” Haden not only accompanies the other musicians, but also stretches the melodic potential of his instrument, particularly in his solo on “Focus on Sanity.” For all the record’s iconoclasm, it swings, and even Coleman’s more outrageous timbral experimentation can be understood as rooted in the expressiveness of the blues.

Image Caption: “The Shape of Jazz to Come” lp cover; Image Credit: Atlantic.

“Crossing Chilly Jordan.” The Blackwood Brothers. (1960)

Known to gospel fans since 1934, the Blackwood Brothers are one of the most popular U.S. Southern gospel quartets. They have been credited with creating enthusiastic audiences in the 1950s and ’60s for music once considered unexciting, dry and boring, and transforming the genre by adding African American musical forms (blues, jazz, black gospel) to their own traditions. Written by quartet member, J. D. Sumner (considered by many to have been the lowest bass in gospel), “Crossing Chilly Jordan,” is an outstanding example of this spirit and style. With its jubilant infectious rhythms, rousing tempo, call-and-response style and four-part harmony, the song was often used as their encore number in live performances. The Blackwood Brothers were inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame in 1998.

Known to gospel fans since 1934, the Blackwood Brothers are one of the most popular U.S. Southern gospel quartets. They have been credited with creating enthusiastic audiences in the 1950s and ’60s for music once considered unexciting, dry and boring, and transforming the genre by adding African American musical forms (blues, jazz, black gospel) to their own traditions. Written by quartet member, J. D. Sumner (considered by many to have been the lowest bass in gospel), “Crossing Chilly Jordan,” is an outstanding example of this spirit and style. With its jubilant infectious rhythms, rousing tempo, call-and-response style and four-part harmony, the song was often used as their encore number in live performances. The Blackwood Brothers were inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame in 1998.

Image Caption: The Blackwood Brothers; Image Credit: RCA..

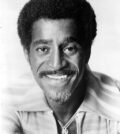

“The Twist.” Chubby Checker. (1960)

Chubby Checker’s rendition of “The Twist” became emblematic of the energy and excitement of the early 1960s. Originally a twelve-bar blues song written and released as a “B” side in 1959 by Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, “The Twist” enjoyed only moderate success until American Bandstand host Dick Clark selected Checker, a young singer from Philadelphia, to record the new version and perform it on his program. Checker’s recording quickly became a hit with teens and the model for many takeoffs. “The Twist” caught on with adults as well when café society worldwide embraced the dance craze even as teens were moving on to new steps, such as “the mash potato” and “the slop.” Frank Sinatra recorded a “Twist” song, “The Flintstones” twisted, and Bob Hope quipped, “If they turned off the music, they’d be arrested.” Reissued in 1962, Checker’s version soared again to the top of the charts, ahead of the other “Twist” records that had inundated the recording industry in the intervening months.

Chubby Checker’s rendition of “The Twist” became emblematic of the energy and excitement of the early 1960s. Originally a twelve-bar blues song written and released as a “B” side in 1959 by Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, “The Twist” enjoyed only moderate success until American Bandstand host Dick Clark selected Checker, a young singer from Philadelphia, to record the new version and perform it on his program. Checker’s recording quickly became a hit with teens and the model for many takeoffs. “The Twist” caught on with adults as well when café society worldwide embraced the dance craze even as teens were moving on to new steps, such as “the mash potato” and “the slop.” Frank Sinatra recorded a “Twist” song, “The Flintstones” twisted, and Bob Hope quipped, “If they turned off the music, they’d be arrested.” Reissued in 1962, Checker’s version soared again to the top of the charts, ahead of the other “Twist” records that had inundated the recording industry in the intervening months.

Image Caption: “The Twist” lp cover; Image Credit: Parkway Records.

“Old Time Music at Clarence Ashley’s.” Doc Watson, Clarence Ashley, et.al. (1960-1962)

Born in Tennessee in 1895, singer/banjoist Clarence Ashley grew up steeped in the folk music of Appalachia, and in the 1920s and 1930s, recorded many classic 78s in the old time style that flourished before bluegrass and modern country music. His music was rediscovered in the 1950s as part of Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, but no one knew he was alive and well until Ralph Rinzler and John Herald met him at old time music contest in 1960. Rinzler arranged to record Ashley, whose band included the much younger Arthel “Doc” Watson, a blind guitarist with similarly deep roots who had also absorbed jazz influences and played in local country and rockabilly bands. Watson turned classic fiddle tunes into blistering guitar showpieces with ease and memorably embellished the old songs he and Ashley sang. These recordings helped make them stars of the folk revival. Over the next fifty years, Watson played all over the world, teaching and inspiring countless young folk musicians.

Born in Tennessee in 1895, singer/banjoist Clarence Ashley grew up steeped in the folk music of Appalachia, and in the 1920s and 1930s, recorded many classic 78s in the old time style that flourished before bluegrass and modern country music. His music was rediscovered in the 1950s as part of Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, but no one knew he was alive and well until Ralph Rinzler and John Herald met him at old time music contest in 1960. Rinzler arranged to record Ashley, whose band included the much younger Arthel “Doc” Watson, a blind guitarist with similarly deep roots who had also absorbed jazz influences and played in local country and rockabilly bands. Watson turned classic fiddle tunes into blistering guitar showpieces with ease and memorably embellished the old songs he and Ashley sang. These recordings helped make them stars of the folk revival. Over the next fifty years, Watson played all over the world, teaching and inspiring countless young folk musicians.

Image Caption: Doc Watson; Image Credit: LOC.

“Hoodoo Man Blues” (album). Junior Wells. (1965)

“Hoodoo Man Blues”is cited as one of the first studio recordings to capture the energy of a Chicago blues club. Delmark Records owner Bob Koester was so anxious to record an album with blues singer and harmonica player Junior Wells that he allowed Wells to choose his sidemen and songs. Because Koester believed the selected guitarist was contractually obligated to another company, guitarist Buddy Guy was billed as “Friendly Chap” on the original LP release. Koester also allowed Wells to stretch out a bit on songs, half of which lasted longer than three and a half minutes at a time when three minutes or less was the norm for a blues record. One bit of bad luck turned out to be a godsend. During the session, Buddy Guy’s amplifier quit working, and while it was being repaired, engineer Stu Black wired him through the Leslie speaker of the studio’s Hammond B-3 organ, which gave Guy’s guitar a distinctive sound, easily noticeable on the title cut. Koester later remarked, “I’ve always been amazed at how rarely reviewers commented on the guitar-organ tracks.”

“Hoodoo Man Blues”is cited as one of the first studio recordings to capture the energy of a Chicago blues club. Delmark Records owner Bob Koester was so anxious to record an album with blues singer and harmonica player Junior Wells that he allowed Wells to choose his sidemen and songs. Because Koester believed the selected guitarist was contractually obligated to another company, guitarist Buddy Guy was billed as “Friendly Chap” on the original LP release. Koester also allowed Wells to stretch out a bit on songs, half of which lasted longer than three and a half minutes at a time when three minutes or less was the norm for a blues record. One bit of bad luck turned out to be a godsend. During the session, Buddy Guy’s amplifier quit working, and while it was being repaired, engineer Stu Black wired him through the Leslie speaker of the studio’s Hammond B-3 organ, which gave Guy’s guitar a distinctive sound, easily noticeable on the title cut. Koester later remarked, “I’ve always been amazed at how rarely reviewers commented on the guitar-organ tracks.”

Image Caption: “Hoodoo Man Blues” lp cover; Image Credit: Delmark.

“Sounds of Silence” (album). Simon and Garfunkel. (1966)

The initial success of Simon and Garfunkel can be traced through the evolution of the title of their first hit record. The original, acoustic version released on their debut album, “Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M.,”was called “The Sounds of Silence.” That album sold poorly and the duo split up. Without their knowledge, Columbia Records producer Tom Wilson overdubbed drums, electric guitar and electric bass for the song’s release as a single. No stranger to merging rock music with folk lyrics, Wilson, that very day, had worked on Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone.” This new version of “Sounds of Silence” climbed the singles charts, prompting Simon and Garfunkel to reunite to record another album, this time in the folk-rock style of their surprise hit. At that point, the title of the single was changed to “The Sound of Silence,” and the album became “Sounds of Silence.” The duo’s Everly Brothers-influenced harmonies remain, augmented by electric guitars, keyboards, drums and even horns. “Somewhere They Can’t Find Me” shows the extent that their sound had changed in such a short time, displaying the influence of British guitarist Davey Graham, who contributed the opening of his now classic “Anji,” also covered on the album. Simon and Garfunkel would continue to grow as artists, but their success began here, with a re-edited single they knew nothing about.

The initial success of Simon and Garfunkel can be traced through the evolution of the title of their first hit record. The original, acoustic version released on their debut album, “Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M.,”was called “The Sounds of Silence.” That album sold poorly and the duo split up. Without their knowledge, Columbia Records producer Tom Wilson overdubbed drums, electric guitar and electric bass for the song’s release as a single. No stranger to merging rock music with folk lyrics, Wilson, that very day, had worked on Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone.” This new version of “Sounds of Silence” climbed the singles charts, prompting Simon and Garfunkel to reunite to record another album, this time in the folk-rock style of their surprise hit. At that point, the title of the single was changed to “The Sound of Silence,” and the album became “Sounds of Silence.” The duo’s Everly Brothers-influenced harmonies remain, augmented by electric guitars, keyboards, drums and even horns. “Somewhere They Can’t Find Me” shows the extent that their sound had changed in such a short time, displaying the influence of British guitarist Davey Graham, who contributed the opening of his now classic “Anji,” also covered on the album. Simon and Garfunkel would continue to grow as artists, but their success began here, with a re-edited single they knew nothing about.

Image Caption: “The Sounds of Silence” lp cover; Image Credit: Columbia.

“Cheap Thrills.” Big Brother and the Holding Company. (1968)

This hotly anticipated album was Janis Joplin’s second release with Big Brother and the Holding Company, and on the disc, her soulful, bluesy singing reaches transcendent heights. Big Brother and the Holding Company was not just a backing band for Joplin, however. Part of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury music scene, they were an excellent psychedelic rock band in their own right that existed before Joplin joined and reformed after she left later that year. James Gurley’s scorching, wildly overdriven guitar solos and the spidery interplay between his and Sam Andrew’s guitars on several track plus the solid rhythm of Dave Getz’s drums all attest to the band’s expertise. The album’s showstopper is the cover of Erma Franklin’s “Piece of My Heart,” which in Joplin’s hands expresses both desperation and endurance. Remarkably, even when her voice seems to be breaking up she stays in tune.

This hotly anticipated album was Janis Joplin’s second release with Big Brother and the Holding Company, and on the disc, her soulful, bluesy singing reaches transcendent heights. Big Brother and the Holding Company was not just a backing band for Joplin, however. Part of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury music scene, they were an excellent psychedelic rock band in their own right that existed before Joplin joined and reformed after she left later that year. James Gurley’s scorching, wildly overdriven guitar solos and the spidery interplay between his and Sam Andrew’s guitars on several track plus the solid rhythm of Dave Getz’s drums all attest to the band’s expertise. The album’s showstopper is the cover of Erma Franklin’s “Piece of My Heart,” which in Joplin’s hands expresses both desperation and endurance. Remarkably, even when her voice seems to be breaking up she stays in tune.

Image Caption: Janis Joplin; Image Credit: Columbia.

“The Dark Side of the Moon.” Pink Floyd. (1973)

“The Dark Side of the Moon”benefits from the fact that Pink Floyd worked out the songs in live performances for months before going into a studio. And when they did, they had some recent technological innovations at their disposal, such as 16-track recorders and synthesizers. Rather than overdoing it, “The Dark Side of the Moon”is an example of brilliant, innovative production in service of the music. The album is notable for the close vocal harmonies of Richard Wright and David Gilmour and for double tracking, both of voices and guitars. More unusual effects include the flanged choir in “Time,” the precisely placed delays in “Us and Them,” and a tape loop at the beginning of “Money” that was so long a microphone stand had to be used to hold it up. Band member Roger Waters interviewed studio staff and others responding to a series of flashcard questions, then used snippets of their answers throughout the album. Befitting its title, the themes of the concept album are dark – madness, violence, greed and the passage of time, culminating in death – as Waters put it, “those fundamental issues of whether the human race is capable of being humane.”

“The Dark Side of the Moon”benefits from the fact that Pink Floyd worked out the songs in live performances for months before going into a studio. And when they did, they had some recent technological innovations at their disposal, such as 16-track recorders and synthesizers. Rather than overdoing it, “The Dark Side of the Moon”is an example of brilliant, innovative production in service of the music. The album is notable for the close vocal harmonies of Richard Wright and David Gilmour and for double tracking, both of voices and guitars. More unusual effects include the flanged choir in “Time,” the precisely placed delays in “Us and Them,” and a tape loop at the beginning of “Money” that was so long a microphone stand had to be used to hold it up. Band member Roger Waters interviewed studio staff and others responding to a series of flashcard questions, then used snippets of their answers throughout the album. Befitting its title, the themes of the concept album are dark – madness, violence, greed and the passage of time, culminating in death – as Waters put it, “those fundamental issues of whether the human race is capable of being humane.”

Image Caption: “The Dark Side of the Moon” lp cover; Image Credit: Capitol.

“Music Time in Africa: Mauritania.” Leo Sarkisian, host. (July 29, 1973)

“Music Time in Africa,” first aired in 1965, is the longest-running English-language show in the history of the Voice of America (VOA), the international news and information broadcasting arm of the United States. The creator and host of the program, Leo Sarkisian, made his first trip abroad to record traditional music in the field in the late 1950s. A one-time artist and music editor, Sarkasian was recruited in 1963 for work at the VOA by Edward R. Murrow, then director of the director of the United States Information Agency (USIA), the organization responsible for communicating U.S. policy abroad and carrying out much of the government’s international information and cultural programs. Over the next 30 years, Sarkasian would record in every nation on the African continent, as well as in Asian countries such as Bangladesh and Pakistan. Letters to Sarkisian from African listeners thanked him for introducing them to music from other African nations. On this representative program from 1973, Sarkisian discusses and presents music recorded in Mauritania. At the time of Sarkisian’s retirement in 2012 at the age of 91, his original library numbered over 10,000 one-of-a-kind reel-to-reel recordings. Housed at VOA headquarters, the Leo Sarkisian Library of African Music (1958-c.1990s) is being digitized by the University of Michigan.

“Music Time in Africa,” first aired in 1965, is the longest-running English-language show in the history of the Voice of America (VOA), the international news and information broadcasting arm of the United States. The creator and host of the program, Leo Sarkisian, made his first trip abroad to record traditional music in the field in the late 1950s. A one-time artist and music editor, Sarkasian was recruited in 1963 for work at the VOA by Edward R. Murrow, then director of the director of the United States Information Agency (USIA), the organization responsible for communicating U.S. policy abroad and carrying out much of the government’s international information and cultural programs. Over the next 30 years, Sarkasian would record in every nation on the African continent, as well as in Asian countries such as Bangladesh and Pakistan. Letters to Sarkisian from African listeners thanked him for introducing them to music from other African nations. On this representative program from 1973, Sarkisian discusses and presents music recorded in Mauritania. At the time of Sarkisian’s retirement in 2012 at the age of 91, his original library numbered over 10,000 one-of-a-kind reel-to-reel recordings. Housed at VOA headquarters, the Leo Sarkisian Library of African Music (1958-c.1990s) is being digitized by the University of Michigan.

Image Caption: Leo Sarkisian; Image Credit: VOA.

“Ramones.” The Ramones. (1976)

Clash cofounder Joe Strummer has stated that the first time he saw The Ramones, the band generated a “white heat” attributable as much to the speed of the songs and volume of the amplifiers as to the fact that “you couldn’t put a cigarette paper between the end of one song and the beginning of the next.” The band’s first album captured the incandescence of guitarist Johnny Ramone’s speedy, no-nonsense guitar work, Tommy Ramone’s propulsive bass, and the surfy sonorities of Deedee’s drums. The youthful tone of Joey Ramone’s singing voice was equally influenced by Iggy Pop and bubblegum rock and when combined with the backing vocals and lyrics portraying teen love and anxiety, gave the album a strong pop flavor despite its heavy sound and the disturbing aspects of other songs dealing with drug use, Nazism and male prostitution. Recorded on a miniscule budget with little separation between instruments, few overdubs and no guitar solos, the album is an early example of a do-it-yourself aesthetic that inspired thousands of teens to form bands. The album’s outsized influence has been cited by first-generation British punkers (Strummer, The Sex Pistols, Captain Sensible of the Damned), hardcore bands (Husker Du, Black Flag, The Minutemen), alternative rockers (Nirvana, Sonic Youth, Soundgarden) and post rockers (Sleater Kinney) alike, over more than three decades of punk rock’s history.

Clash cofounder Joe Strummer has stated that the first time he saw The Ramones, the band generated a “white heat” attributable as much to the speed of the songs and volume of the amplifiers as to the fact that “you couldn’t put a cigarette paper between the end of one song and the beginning of the next.” The band’s first album captured the incandescence of guitarist Johnny Ramone’s speedy, no-nonsense guitar work, Tommy Ramone’s propulsive bass, and the surfy sonorities of Deedee’s drums. The youthful tone of Joey Ramone’s singing voice was equally influenced by Iggy Pop and bubblegum rock and when combined with the backing vocals and lyrics portraying teen love and anxiety, gave the album a strong pop flavor despite its heavy sound and the disturbing aspects of other songs dealing with drug use, Nazism and male prostitution. Recorded on a miniscule budget with little separation between instruments, few overdubs and no guitar solos, the album is an early example of a do-it-yourself aesthetic that inspired thousands of teens to form bands. The album’s outsized influence has been cited by first-generation British punkers (Strummer, The Sex Pistols, Captain Sensible of the Damned), hardcore bands (Husker Du, Black Flag, The Minutemen), alternative rockers (Nirvana, Sonic Youth, Soundgarden) and post rockers (Sleater Kinney) alike, over more than three decades of punk rock’s history.

Image Caption: “Ramones” lp cover; Image Credit: Sire.

“Wild Tchoupitoulas.” The Wild Tchoupitoulas. (1976)

“Ain’t nothin’ but a party, y’all” intones George Clinton on the title track of this lively and unbelievably rhythmic funk album. While this undeniably is a party record, it is also rooted in the deepest currents of African-American musical culture and history. For example, the words “Swing down, sweet chariot/Stop, and let me ride” are an unmistakable reference to the influential spiritual recorded by the Fisk Jubilee Singers. The album was released in late 1975 shortly after the arrival to Parliament of saxophonist Maceo Parker and trombonist and arranger extraordinaire Fred Wesley. Like Parker and Wesley, bass player Bootsy Collins, dubbed by one critic a “bass deity,” had played with pioneer of funk James Brown. Add to such assembled talent the classically trained Bernie Worrell whose synthesizer conjures galaxies of cosmic sound, but whose piano, as heard on the track “P-Funk,” evokes the ethereal chords of jazz pianist McCoy Tyner. DJ, conductor, arranger and wild lyricist George Clinton oversees the whole, providing an amazing range of space characters (Lollipop Man, Star Child) outlandish vocabulary (“supergroovalistic,” “prosifunkstication”) and all-around funkiness. The album has had an enormous influence on jazz, rock and dance music.

“Ain’t nothin’ but a party, y’all” intones George Clinton on the title track of this lively and unbelievably rhythmic funk album. While this undeniably is a party record, it is also rooted in the deepest currents of African-American musical culture and history. For example, the words “Swing down, sweet chariot/Stop, and let me ride” are an unmistakable reference to the influential spiritual recorded by the Fisk Jubilee Singers. The album was released in late 1975 shortly after the arrival to Parliament of saxophonist Maceo Parker and trombonist and arranger extraordinaire Fred Wesley. Like Parker and Wesley, bass player Bootsy Collins, dubbed by one critic a “bass deity,” had played with pioneer of funk James Brown. Add to such assembled talent the classically trained Bernie Worrell whose synthesizer conjures galaxies of cosmic sound, but whose piano, as heard on the track “P-Funk,” evokes the ethereal chords of jazz pianist McCoy Tyner. DJ, conductor, arranger and wild lyricist George Clinton oversees the whole, providing an amazing range of space characters (Lollipop Man, Star Child) outlandish vocabulary (“supergroovalistic,” “prosifunkstication”) and all-around funkiness. The album has had an enormous influence on jazz, rock and dance music.

Image Caption: “Wild Tchoupitoulas” lp cover; Image Credit: Island Records.

“Saturday Night Fever.” The Bee Gees, et.al. (1977)

“Saturday Night Fever,” the soundtrack to the popular movie starring John Travolta, was released in November 1977 as the disco dance craze was in decline. The popularity of the album, featuring the Bee Gees trademark falsettos over vibrant and infectious beats, was a major factor in reversing that course. More than 20,000 discotheques opened during the next year, attracting some 36 million patrons, according to one estimate. Following “Saturday Night Fever’s” success, disco records became a major component of the music business. Along with the Brothers Gibb, this disco masterpiece features songs by Tavares, Yvonne Elliman, K.C. & The Sunshine Band, and Kool & The Gang.

“Saturday Night Fever,” the soundtrack to the popular movie starring John Travolta, was released in November 1977 as the disco dance craze was in decline. The popularity of the album, featuring the Bee Gees trademark falsettos over vibrant and infectious beats, was a major factor in reversing that course. More than 20,000 discotheques opened during the next year, attracting some 36 million patrons, according to one estimate. Following “Saturday Night Fever’s” success, disco records became a major component of the music business. Along with the Brothers Gibb, this disco masterpiece features songs by Tavares, Yvonne Elliman, K.C. & The Sunshine Band, and Kool & The Gang.

Image Caption: “Saturday Night Fever” lp cover; Image Credit: RSO.

“Einstein on the Beach.” Phillip Glass, Robert Wilson. (1979)

Influenced by non-Western music and avant-garde theater, composer Philip Glass and theater director Robert Wilson created “Einstein on the Beach,” the nearly five-hour opera that brought both international renown, incorporating visual images, dance, a chorus of untrained singers, and performers dressed as Albert Einstein. Characterized by one reviewer as “a heterogeneous surreal entertainment of ‘spectacle’ and ‘event,’” “Einstein on the Beach,” though lacking in narrative action, provides a series of “living pictures” divided into four acts, nine scenes and five connecting “knee plays,” and revolves around three recurring visual images: trains, a trial and a spaceship, each with corresponding music. Glass has written, “My main approach throughout has been to link harmonic structure directly to rhythmic structure, using the latter as a base.” Premiering in 1976, the opera, called a “mixture of mathematical clarity and mystical allure” by New York Times reviewer John Rockwell, was performed by an ensemble of amplified wind, voices and keyboards, as well as violin solos, solo soprano arias and a cappella choruses.

Influenced by non-Western music and avant-garde theater, composer Philip Glass and theater director Robert Wilson created “Einstein on the Beach,” the nearly five-hour opera that brought both international renown, incorporating visual images, dance, a chorus of untrained singers, and performers dressed as Albert Einstein. Characterized by one reviewer as “a heterogeneous surreal entertainment of ‘spectacle’ and ‘event,’” “Einstein on the Beach,” though lacking in narrative action, provides a series of “living pictures” divided into four acts, nine scenes and five connecting “knee plays,” and revolves around three recurring visual images: trains, a trial and a spaceship, each with corresponding music. Glass has written, “My main approach throughout has been to link harmonic structure directly to rhythmic structure, using the latter as a base.” Premiering in 1976, the opera, called a “mixture of mathematical clarity and mystical allure” by New York Times reviewer John Rockwell, was performed by an ensemble of amplified wind, voices and keyboards, as well as violin solos, solo soprano arias and a cappella choruses.

Image Caption: Philip Glass; Image Credit: Tomato.

“The Audience with Betty Carter.” Betty Carter. (1980)

In 1969, after 20 years as a professional jazz singer that were sometimes frustrating, Betty Carter took the difficult and risky step of starting her own label, Bet-Car Records. It proved fortuitous for her, as once she was in charge of her own recording, she entered the most productive and successful phase of her career. Her double album, “The Audience with Betty Carter,” was recorded with her instrumental trio during a three night engagement at San Francisco’s Keystone Korner, one of her favorite venues, and the material is divided between her original compositions like “Sounds (Movin’ On),” her 25-minute tour de force of improvisation and scat singing; and an eclectic mix of standards such as “The Trolley Song,” “My Favorite Things,” and more obscure gems such as Charles Henderson and Rudy Vallee’s “Deep Night.” Throughout, one can appreciate the special rapport with her musicians and listeners that informed her live performances, and which enabled her to gain recognition as a superlative musician during a lean era for jazz singers.

In 1969, after 20 years as a professional jazz singer that were sometimes frustrating, Betty Carter took the difficult and risky step of starting her own label, Bet-Car Records. It proved fortuitous for her, as once she was in charge of her own recording, she entered the most productive and successful phase of her career. Her double album, “The Audience with Betty Carter,” was recorded with her instrumental trio during a three night engagement at San Francisco’s Keystone Korner, one of her favorite venues, and the material is divided between her original compositions like “Sounds (Movin’ On),” her 25-minute tour de force of improvisation and scat singing; and an eclectic mix of standards such as “The Trolley Song,” “My Favorite Things,” and more obscure gems such as Charles Henderson and Rudy Vallee’s “Deep Night.” Throughout, one can appreciate the special rapport with her musicians and listeners that informed her live performances, and which enabled her to gain recognition as a superlative musician during a lean era for jazz singers.

Image Caption: “The Audience with Betty Carter” lp cover; Image Credit: Betcar, Verve.

0 comments