- Cirque du Soleil’s “Crystal” at Fishers Event Center, a photo preview

- The Gatlin Brothers at Brown Country Music Center

- The Black Keys will perform at Innings Festival, Feb 21.

- Gary Clark Jr. will rock the Innings Festival 2025

- Fall Out Boy to appear at Innings Festival in February

- Kris Kristofferson passes away at 88

An Appointment With The Waterboys

After finishing up high school in June of 1988 I took a job at a record store in my local mall, called A&A Records, to supplement my growing but still sparse gigging income. A&A Records was in the late ‘80s perhaps Canada’s largest record store chain, and as such carried all the latest releases. During my year or so working there I was fortunate enough to intercept such great new albums as the first Traveling Wilburys release, the Cowboy Junkies’ Trinity Sessions, CSNY’s American Dream, R.E.M’s Green, Tracy Chapman’s debut, and a rather unique oddity called Fisherman’s Blues by a band named the Waterboys.

At 17 years old, having grown up in a non-descript Newfoundland suburb, I really had no clue about a lot of music except for the standard classic rock catalogue. Therefore, I had never heard of the Waterboys. Spinning the record on the store’s turntable, I was somewhat confused. The title track was a song about wanting to be a fisherman, and it rollicked about in a way that was akin to the traditional music of Newfoundland. This initially did not impress me. I thought, “who are these squares playing my grandfather’s music?” Then the next track was a more rock-oriented affair that had an overdriven fiddle thrown into the mix with a thumping bass. I was mind-boggled. The best way I could describe it was “trad-rock,” and this was before it became an actual genre. Bob Hallett from Great Big Sea once accurately described Fisherman’s Blues to me as “the record that spawned a thousand pub bands.”

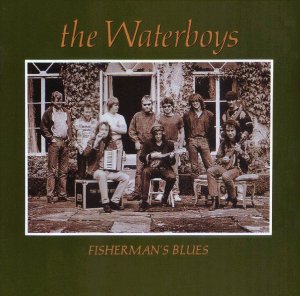

Not only was the album’s music confusing; the photo on the cover was just downright odd in the grand scheme of evocative album covers. Here, in a frame surrounded by green, was a group of guys just sort of hanging around outside a rustic building of some sort. They were posed as if for a family photo or picture of a rugby team. Some of them looked like musicians, while others looked like they were there to fix the plumbing or do some drywall. Were all these guys in the actual band? The only discernible leader (not that these guys looked like they wanted or needed one) was a guy seated center with a mandolin, hat, long hair, scruffy beard, and a coy grin. That guy looked like he meant business. After a few listens, the album sort of faded from my life. Temporarily.

When I moved to Ottawa in spring of 1989, the roommate of a friend of mine inadvertently reintroduced me to the Waterboys. He had an album called This is the Sea. I heard the music emanating from his basement room, and instantly recognized that voice: expressive, emotive, enigmatic, full of bravado and hope. It had a recognizable accent that lilted on phrases and punctuated certain lines. I remembered it from the record store. Learning that the band had roots in punk and new wave gave me a whole different perspective on Fisherman’s Blues. What I thought was a band in established form was actually a group in departure of style. Experimental. And there was so much else going on here lyrically than my teenage lack of experience could ever see before.

Moving back to Newfoundland in the fall of 1990, I started to write songs and play solo at the local bars. Of course I couldn’t get away with singing all my own shitty, juvenile songs; therefore, I amassed a collection of cover songs that I thought would go over well. By this point, Fisherman’s Blues had become very popular – especially on my turntable and that of my friends. I learned every song on that record except the fiddle tunes, and played them faithfully night after night to the drunken audiences of St. John’s. They all went over great: “Hank,” “And a Bang on the Ear,” “Strange Boat,” When Will We Be Married,” etc. And when someone asked for a traditional tune I played a Waterboys song; I had no other trad tunes in my repertoire, and these songs really saved my ass on more than one occasion.

As a burgeoning songwriter, I began to take notice of the art and craftsmanship of these Waterboys songs. Slowly but surely Mike Scott took his place right alongside of Bob Dylan and Neil Young in my psyche as a guiding force in my songwriting pursuits. One of my most important discoveries about Mike Scott’s writing style was his use of figurative language. I was slightly embarrassed for myself when I realized that “Fisherman’s Blues” has nothing to do with fishing. Lyrics such as “Casting out my sweet line with abandonment and love” and “crashing headlong into the heartland like a canon in the rain” are about taking life by the nuts and embracing all the uncertainties with reckless abandon. The fisherman and the brakeman in this song are merely symbolic talismen to this idealistic nirvana so many of us want to embrace yet are held back by fear. The language is infused with powerful metaphor, thought provoking imagery, and alliteration made that much more potent by enthusiastic vocal punctuations. Mike Scott made me endeavour to write meaningful lyrics that might one day stir others’ emotions as his songs did mine.

[youtube id=”YP4I1W4IEew” width=”620″ height=”360″]

In 1995 I discovered Mike Scott’s solo album Bring ‘em All In. I became transfixed by songs such as “She is so Beautiful” and “What do you Want Me To Do,” and I was impressed by the sparse instrumentation: just some guitars with keys and percussion peppered here and there. This was in essence a true songwriter album, more so than any of the Waterboys’ records. Here Scott was tapping into his original influences: Lou Reed, Patti Smith, Dylan. The album may not have made it as big commercially as some of the Waterboys’ material, but for everyone I knew it was a true gift at just the right time. And it was every bit as exciting as the Waterboys, with an added bonus of lyrics that were even more articulate and emotive than anything he had yet written.

[youtube id=”4PLhT0WIgwU” width=”620″ height=”360″]

In the ensuing years I lost track of Scott’s activities, becoming more and more immersed in making my first album Too Commercial in 1997 and trying to get a break in the Canadian music scene. Scott was always in the back of my mind, however, and after the explosion of the worldwide web I started casually keeping track of what he was doing again. Following him on the social networking site Twitter, I gleaned from his tweets his cutting sense of humor and also cruel judgment of any music he deems “soft rock” or otherwise unworthy of his praise. This candor sort of made me recoil at times because of its brutal honesty. But of course it makes sense that any expression from Mike Scott will no doubt inspire emotions of some sort. It’s what he does best.

A few weeks ago I received an invitation by friend John Steele to an event he and his brother Rob were hosting – simply and vaguely presented on the invitation as “Dinner and a Very Special Musical Guest.” Despite the lack of specific information, I readily accepted the invitation. Knowing John as a casual acquaintance for many years, I knew him to be an aficionado of quality music. Therefore, I knew that whatever he was involved with musically would be great. John Steele, like Mike Scott, doesn’t suffer musical fools gladly. He even admonished me in a good-natured way for writing in my blog about Canadian icons Chilliwack, whom he would understandably consider too mainstream compared to artists such as Dylan and Steve Earle whose careers have headed irrevocably toward the outer reaches of commercialism.

Last night my wife Michelle and I headed to the Capital Hotel for the event. Meeting lots of people in the lobby we knew, we asked around to see if anyone had heard who was going to be playing. No one knew! It was enticing.

We were soon ushered into a salon and fed a delicious buffet dinner with complimentary bottles of wine and delectable dessert. John and his brother Rob mingled and made sure their guests were all happy and fed before inviting them into the neighbouring salon where the room was beautifully adorned with pipe-and-drape and subtle lighting. A simple stage was set up with sparse instrumentation and a few microphones. After everyone was seated, John took to the stage to introduce the opening act, a “New York legend” who “sang on the last Bruce Springsteen record.” John said he and his brother had just come back from New York where this guy was treated like the mayor in local cafes and bars. It was New Yorker Willie Nile, a rollicking singer-songwriter who is not well-known with the general population but revered by both fellow musicians and devout music fans. MuchMusic’s Mike Campbell first turned me on to Nile in 1995 when he played me one of Nile’s albums. I loved the song “Vagabond Moon,” and it was only a few months prior to this night that I had gone on youtube to search for him. I found footage of him in concert, with none other than Bruce himself sitting in as a special guest.

Nile, joined by Gloryhound guitarist Evan Meisner from Halifax, played an inspired acoustic set that warmed up the crowd nicely. Nile, an engaging character with a commanding stage presence that belies decades of experience, told some great stories and seemed genuinely excited to be there. After his set, he eagerly grabbed a table at the back of the room and joined the anticipatory crowd patiently awaiting the mystery guests.

Following a quick break for people to avail of the can and to refill their drinks, John once again took the stage to announce the headliners. He described them as a band whom many people in the audience would remember from their 1983 debut release up through the years of solo albums and eventual reunions. Then he said it: “Ladies and gentleman, please welcome…the Waterboys!” An astonished collective gasp mingled with raucous applause as Mike Scott and legendary fiddler Steve Wickham took the stage, tuned, and barreled into a long set of classics, traditional standards, and a even a reading or two from Scott’s autobiography Adventures of a Waterboy. These book excerpts were particularly evocative in their mixture of poetic diction and precision storytelling. As a literature professor I enjoyed them perhaps as much as the music; I made a mental note, in the fortunate possible case of meeting him later, to ask where he had managed to learn to write prose with the same profiency as he writes songs. I didn’t get to ask that question. However, I did get a whole lot more than I bargained for as the night drew on.

Following their set, Scott and Wickham did their obligatory meet and greet with the lingering fans. Larry Foley gave Scott a hand-written copy of the extra verse he had added to his rendition of “Fisherman’s Blues.” Scott enthusiastically read the verse, and giving Larry a smile he folded it and put in the inside pocket of his blazer. Larry then introduced me to him and we had brief casual words before he and Wickham made their way to the hotel elevators with John and Rob.

Erin’s Pub’s new owners Bob Hallett and Chris Andrews invited all the remaining stragglers downtown for post-show drinks. Shortly after we got there and settled in to watch Dave Panting play a solo set, who should grace the entrance but Scott and Wickham themselves…with instruments on their shoulders. Whispers went around the bar that they were interested in having a “session,” which in trad-speak means sitting around a table with acoustic instruments and playing traditional tunes in an unrestricted, free-flowing style while trading solos and such. Some of Newfoundland’s best trad musicians happened to also be in the pub, so along with Scott and Wickham they gathered at a table in front of the bar by the window and settled in for a session. And what a session it was.

The small audience of about 20 people gathered around at a respectful distance as both sides of the Atlantic merged in song. Lacking any kind of deep knowledge about trad music, I was in awe at the fact that the Newfoundland musicians knew most of the same jigs and reels as the Waterboys and vice versa. Both contingents freely and effortlessly joined together for rowdy renditions of tunes that came second nature to them in delivery. Every so often a musician or two had to lean in to get the key or the time signature, but soon after that they’d be off to the races again. Scott and Wickham even had a choreographed jump that they did in intervals throughout one tune. This sent the small but appreciative audience into a frenzy.

Larry Foley, who had been acting as a de facto master of ceremonies for this session, passed me his guitar about an hour into the session. I was at a loss as to what to play. Billy Sutton suggested I do one of my own called “Your Voice.” I did, and tried to hide my excitement at the fact that in the chair right next to me sat Mike Scott, a huge influence on my songwriting, picking along intently. After the song was over I passed the guitar along to another singer and sat down in between Scott and Wickham. After a few more tunes, Scott stood up to put his coat on; this symbolically signaled the end of the session. I told him as he tucked his Taylor guitar into his gig bag that it had been a pleasure playing with him and that he has been a big influence on my writing. He said a heartfelt thanks, and then said he thought the tune I played was great as well. “Very nice song,” he said. Truly humbled, I shyly replied, “Really?” He smiled and said, “I played right along with you, didn’t I?”

As the crowd thinned out and the musicians left in cabs for home, I went to the bar to have one last beer with the few musicians remaining. There wasn’t much to say besides “wow, did that really happen?” Fortunately for us, yes it did.

On the way home I thought of John Steele’s words when introducing the Waterboys and how he stressed that the music of this band had united all the music fans in the room when they had first heard it as teenagers all those years ago. It was especially poignant that it also resulted in an unforgettable session that featured a blending of trad, country, and rock genres, uniting the musicians of this province with two ambassadors from across the ocean.

There was no way I could have known as a 17-year-old record store clerk that this strange green album with a bunch of hooligans hanging out on the cover would ever play itself out in such a revelatory way 24 years later.

One Comment